There are lot of people designing algorithms to solve very hard problems efficiently. When we say efficiently we mean spending as few resources as possible, and with resources we mean time and memory (mainly). But how do we know whether some algorithm is the best one? How to know whether certain algorithm cannot be improved any further? In this post I am going to talk about how to prove an algorithm is as good as can be.

Requirements and some notes

I assume you have some knowledge about big-O notation and algorithm design.

In this post I focus on time complexity, so I am going to give you some methods to demonstrate an algorithm is "as fast as can be". Some of that ideas are also applicable to memory complexity analysis.

When I say that an algorithm A such that T(A) = O(f(x)) (i.e runtime complexity function of algorithm A is O(f(x))) cannot be improved any further, I mean that there is no an equivalent algorithm B such that T(B) = O(g(x)) and T(A) != O(g(x)) (i.e runtime complexity function of algorithm A is worse than O(g(x))).

Most of the time you'll be required to design an algorithm that run in a certain amount of time for a certain bounded input. So in most cases you don't need to find an optimum algorithm. But this post will give you some tricks you can use to decide whether you should try to fulfill the requirements or just change your requirements since it can be proved that those requirements are impossible to fulfill.

First with no "tricks" at all

I'm going to talk about some "tricks" in the next sections but let's talk about the straight way first. Given the problem, and some restrictions maybe, let's demonstrate we can't design an algorithm that ran (asymptotically) faster than a given one.

I'll just ilustrate one of those demonstrations. Let's demonstrate that it's not possible to sort a list doing just comparisons between the elements of the list in less than O(n * log n).

The proof

A permutation of a set of elements is an arrangement of those elements. For a set of size n there are n! different arrangements (n*(n-1)*...*2*1). So the task is, given a permutation, how to find the sorted permutation using just comparisons? When I say using just comparisons I mean that the only way to gain some knowledge about the input permutation is by comparing two elements of that permutation.

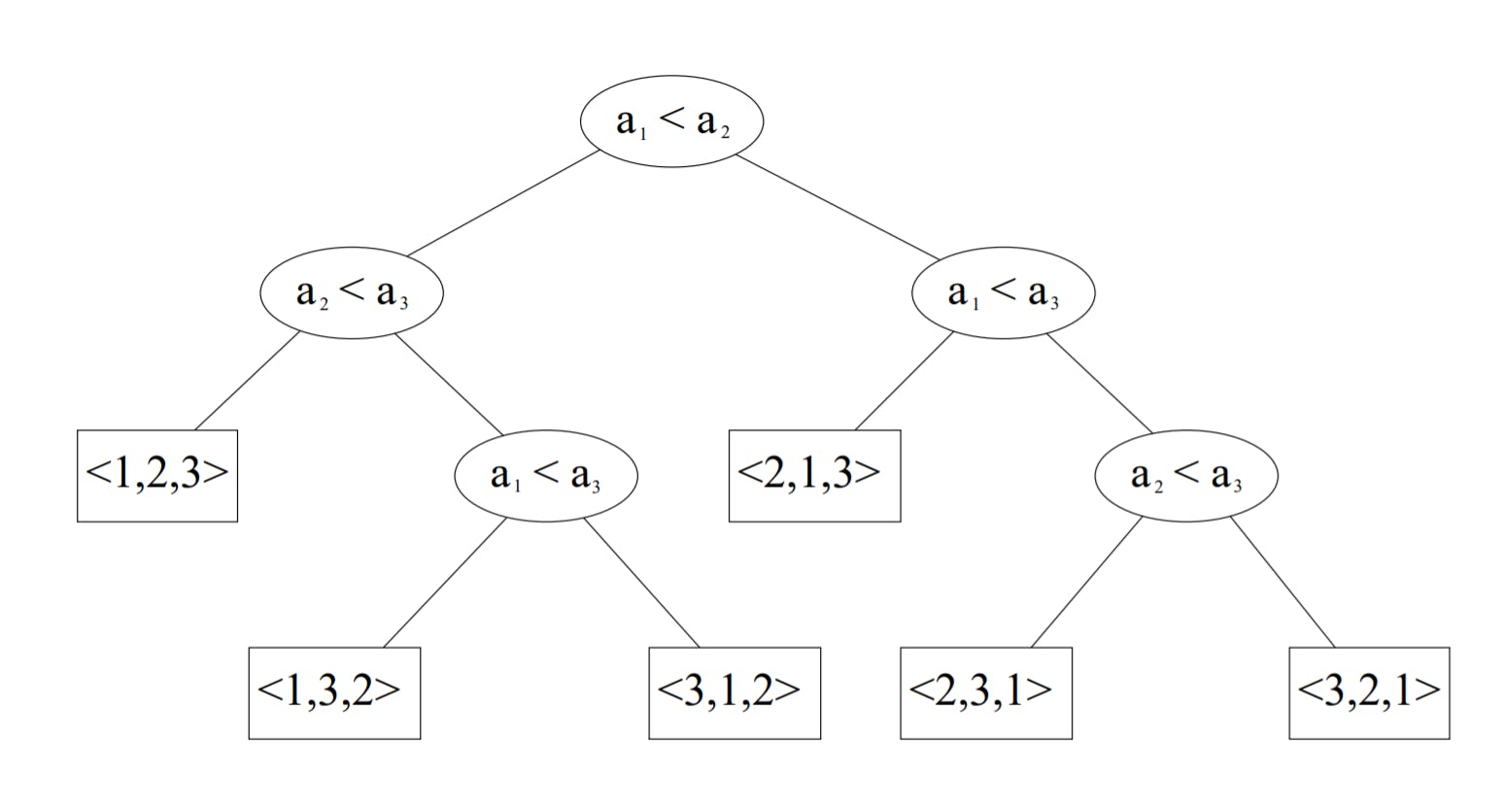

We'll represent such comparison-based algorithm as a binary tree, where the leaves are the different permutations and every interior node represents a comparison between two specific elements of the input. Here's an example of a tree for an input of length 3.

So we start doing the comparison represented in the root, if the answer is "yes", then we know the permutation we're looking for is in the left subtree, otherwise it's in the right subtree. We continue applying the comparisons until we reach a leaf, which represents the sorted permutation.

For example the leaf

<2,3,1>represents the permutation where the first element of the input is in the third position, the second element is in the first position and the third element is in the second position.

Then the length of the path from the root to one of the leaves is the amount of comparisons that we need to do to sort an specific input permutation. So, the longest possible path represents the worst case since by following it we need to do the bigger amount of comparisons. Let's demonstrate that the longest path will always contain at least O(n * log n) comparisons.

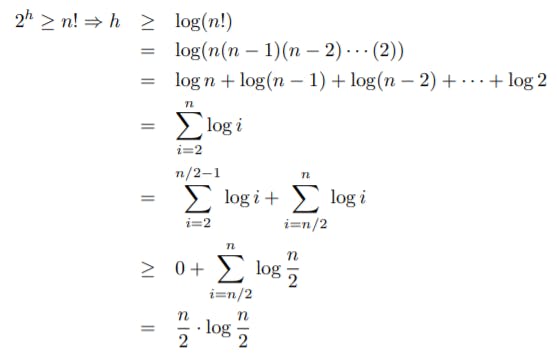

We know the number of different permutations is n! so that's the same number of different leaves in the tree. But if the longest path in the tree has length h then the number of leaves cannot exceed 2^h (2 to the power of h). Then we can apply some math like it's shown in the image.

And that n/2 * log(n/2) is O(n*log n).

So here we represented the algorithm operations through an abstraction (a binary tree) and based on that we demonstrated that there is always a case in wich the algorithm has to make certain amount of operations (O(n * log n)), thus we'll never get an equivalent algorithm that can do less than that certain amount of operations.

Does that mean that we can't sort in less than

O(n * log n)? No! We assumed that the algorithm just makes comparisons to gain knowledge about the input (like bubble sort, quick sort and merge sort do). But there are sorting algorithms that assume some prior knowledge about the input and can sort inO(n)! Take a look at counting sort and radix sort.

The adversary trick

The first "trick" I'm going to talk about is known as the "Adversarial Lower Bound Technique". Now, there will be an adversary (or devil) D. The adversary has access to all the possible inputs, and we'll see the execution of the algorithm A as a game in which D is suposed to select one input, then A will ask for the result of one operation on the input to D, and D must answer the result. The game ends when A has an output given the input D has selected.

The trick here is that D can always change its mind about the input as long as at the end of the game the input selected by D was consistent with the answer D gave throughout the game. The task is to design an adversary strategy that forces A to ask at least as many times as we want.

Example

Let's consider the problem of finding the maximum in a list of length n. The algorithm A is allowed to ask whether the number at a certain position in the list is greater than the current maximum, assuming that the initial maximum is the number at a certain fixed position in the list. Let's prove that D can force A to make at least n-1 operations.

The strategy of D would be place in every position A asks about, a bigger number every time. And the answer will always be "NO" (i.e the number your asking about is not greater than the current maximum). So, after n-1 operations A can state that the maximum is the number in the position it has not asked about.

Let's consider the problem for a list of length 4. The initial maximum will be the number in the first position. Then A asks to D whether the second number is greater than the current maximum. D answers "NO" and puts the number 1 in the second position of the list. Then A asks whether the third number is greater than the current maximum and D answers "NO" and put the number 2 in the third position of the list. Finally A asks about the fourth position and D answers again "NO" and put the number 3 in that position, but then A can state that the maximum is the first number since there is no other number greater than it, then D put a 4 in the first position and shows the input to A. That input (4, 1, 2, 3) is consistent with all the answers D gave to A so we found a case where A is forced to make 3 operations to find the maximum in a list of 4 elements.

The demonstration for a list of n elements is just a generalization of the method described above.

This was a simple example. You can try to prove the lower bound of sorting algorithms described in the previous section via Adversary Technique for a more challenging demonstration.

Problem reduction

The last "trick" I am going to talk about is the Problem Reduction Technique. The idea in this case is to prove that if we could solve certain problem in time less than T(n) then we could solve another problem in a time we already know is impossible.

For example, we have the problem of the Epsilon Distance, which is about telling whether in a list of numbers there are two elements x and y such that |x-y| < e for a fixed e. This problem is known to have a runtime complexity that is O(n * log n) where n is the length of the list. We won't prove that in this article.

Instead we are going to prove that the problem of finding the closest pair of points among a set of n points in a plane cannot be solved with less than O(n * log n) operations.

Supose we can solve the Closest Pair of Points Problem in less than O(n * log n). Now think about the Epsilon Distance Problem, if we have a list of n numbers x1, x2, ..., xn, then we can transform that list into (x1, 0), (x2, 0), ..., (xn, 0). That transformation can be done with O(n) operations. Then we can solve the Closest Pair of Points Problem in less than O(n * log n) and if the distance between those points is less than e we can answer "YES", otherwise we answer "NO". And we have solved the Epsilon Distance Problem with less than O(n * log n) operations. But that's impossible! Since we know that O(n * log n) is the lower bound for solving that problem. Hence, we cannot solve the Closest Pair of Points Probem with less than O(n * log n) operations neither.

NP-completeness

Before the end of this article I want to talk about problems that are NP-complete. Making an oversimplification we'll say that an NP-complete problem is a problem for which we haven't found a solution that makes a polynomial amount of operations. So, until now, the known lower bound for the amount of operations those solutions perform is an exponential function of the input.

Maybe you have heard about NP-complete problems before, and probably you have been told that if one can find a polynomial solution for any of those problems then you'd be proving that all of them have a polynomial solution as well (and then you'd be solving one of the hardest problems in the history of humanity, and your name would be written in any single book about computer science, and you'd be millionare, among other benefits).

That's because the way we can prove that a problem is NP-complete is by proving that if we find a polynomial solution for the problem then we can solve another already known NP-complete problem in polynomial time. In other words, to prove a problem is NP-complete we use the reduction "trick" we've seen in the previous section.

Note that in this case we are not proving that a better runtime is not possible, we are just proving that the humanity hasn't found a polynomial solution for that problem so far.

Maybe you are wondering how the first NP-complete problem was discovered. Well, I can tell you when: 1971. I also can tell you who: Stephen Cook. I even can tell you what: the 3-SAT problem. But the how is up to you.

Conclusions

Proving the lower bound in runtime complexity of an algorithm can be a very dificult task. In this post I have talked about some examples and "tricks" to do so.

I have made a lot of oversimplications all along the article. If you want to learn about this topic in a more technical and formal way you can search other good sources in internet. You can also leave your comment with any doubt or recommendation. You also can @-me on Twitter to start a fruitful debate or you can follow me for some tweets about computer science.