Greedy algorithms try to find the optimal solution by taking the best available choice at every step. For example, you can greedily approach your life. You can always take the path that maximizes your happiness today. But that doesn't mean you'll be happier tomorrow.

Similarly, there are problems for which greedy algorithms don't yield the best solution. Actually, they might yield the worst possible solution. But there are other cases in which we can obtain a solution that is good enough by using a greedy strategy.

In this article, I'll write about greedy algorithms and the use of this strategy even when it doesn't guarantee to find an optimal solution.

The next section is an introduction to greedy algorithms and well-known problems that are solvable using this strategy. Then I'll talk about problems in which the greedy strategy is a really bad option and finally, I show you an example of a good approximation through a greedy algorithm.

Note: Most of the algorithms and problems I discuss in this article include graphs. It would be good if you are familiarized with graphs to get the most out of this post.

Greedy algorithms

Greedy algorithms always choose the best available option. In general, they are computationally cheaper than other families of algorithms like dynamic programming, or brute force. That's because they don't explore the solution space too much. And, for the same reason, they don't find the best solution to a lot of problems.

But there are lots of problems that are solvable with a greedy strategy, and that strategy is precisely the best way to go.

One of the most popular greedy algorithms is Dijkstra's algorithm to find the path with the minimum cost from one vertex to the others in a graph. This algorithm finds such a path by always going to the nearest vertex. That's why we say it is a greedy algorithm.

This is a pseudocode of the algorithm. I denote with G the graph and with s the source node.

Dijkstra(G, s):

distances <- list of length equal to the number of nodes of the graph, initially it has all its elements equal to infinite

distances[s] = 0

queue = the set of vertices of G

while queue is not empty:

u <- vertex in queue with min distances[u]

remove u from queue

for each neighbor v of u:

temp = distances[u] + value(u,v)

if temp < distances[v]:

distances[v] = temp

return distances

After running the previous algorithm we get a list distances such that distances[u] is the minimum cost to go from node s to node u.

This algorithm is guaranteed to work only if the graph hasn't edges with negative costs. A negative cost in an edge can make the greedy strategy to choose a path that is not optimum.

Another example that is used to introduce the concepts of the greedy strategy is the Fractional Knapsack.

In this problem, we have a collection of items. Each item has a weight Wi greater than zero, and a profit Pi also greater than zero. We have a knapsack with a capacity W and we want to fill it in such a way that we get the maximum profit. Of course, we cannot exceed the capacity of the knapsack.

In the fractional version of the knapsack problem, we can take either the entire object or only a fraction of it. When taking a fraction 0 <= X <= 1 of the i-th object, we obtain a profit equal to X*Pi and we need to add X*Wi to the bag. We can solve this problem by using a greedy strategy. I won't discuss the solution here. If you don't know it I recommend you try to solve it by yourself and then look for the solution online.

The number of problems that we can solve by using greedy algorithms is huge. But the number of problems that we cannot solve this way is even bigger. The next section is about the latter ones.

When being greedy is the worst

In the previous section, we saw two examples of problems that are solvable using a greedy strategy. This is great because those are pretty fast algorithms.

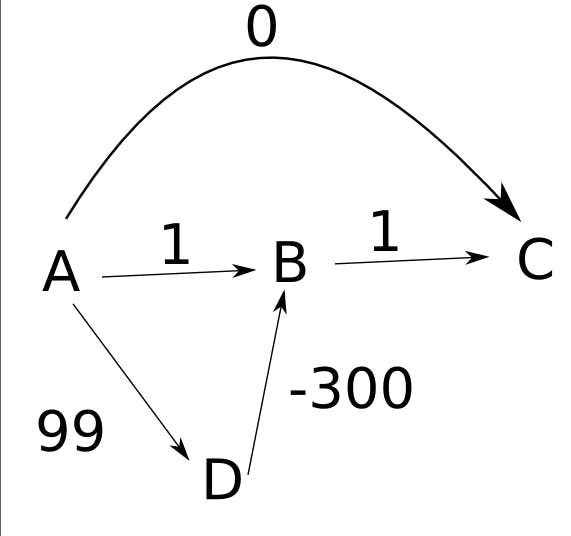

But, as I said, Dijkstra's algorithm doesn't work in graphs with negative edges. And the problem is even bigger. I can always build a graph with negative edges in a way that Dijkstra's solution was as bad as I wanted! Consider the following example that was extracted from Stackoverflow

Dijkstra's algorithm fails to find the distance between A and C. It finds d(A, C) = 0 when it should be -200. And if we decrease the value of the edge D -> B, we'll obtain a distance that we'll be even farther from the actual minimum distance.

Similarly, when we can't break objects in the knapsack problem (the 0-1 Knapsack Problem), the solution that we obtain when using a greedy strategy can be as bad as we want. We always can build an input to the problem that makes the greedy algorithm to fail badly.

Another example is the Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP). Given a list of cities and the distances between each pair of cities, what is the shortest possible route that visits each city exactly once and returns to the origin city?

We can greedily approach the problem by always going to the nearest possible city. We select any of the cities as the first one and apply that strategy.

As happened in previous examples, we can always build a disposition of the cities in a way that the greedy strategy finds the worst possible solution.

In this section, we have seen that a greedy strategy could lead us to disaster. But there are problems in which such an approach can approximate the optimal solution quite well.

When being greedy is not that bad

We have seen that greedy strategy is as bad as we want for some problems. This means that we cannot use it to obtain the optimal solution nor even a good approximation to it.

But there are some examples in which greedy algorithms provide us with very good approximations! In these cases, the greedy approach is very useful because it tends to be cheaper and easier to implement.

The vertex cover of a graph is the minimum set of vertices such that every edge of the graph has at least one of its endpoints in the set.

This is a very hard problem. Actually, there isn't any efficient and exact solution for it. But the good news is that we can make a good approximation with a greedy algorithm.

We select any edge <u, v> from the graph, and add u and v to the set. Then, we remove all the edges that have u or v as one of their endpoints, and we repeat the previous process while the remaining graph had edges.

This might be a pseudocode of the previous algorithm.

vertexCover(G):

VertexCover <- {} // empty set

E' <- edges of G

while E' is not empty:

VertexCover <- VertexCover U {u,v} where <u,v> is in E'

E' = E' - {<u, v> U edges incident to u, v}

return VertexCover

As you can see, this is a simple and relatively fast algorithm. But the best part is that the solution will always be less or equal to two times the optimal solution! We'll never obtain a set that is bigger than two times the smaller vertex cover, no matter how the input graph was built.

I'm not going to include the demonstration of this statement in this post, but you can prove it by noticing that for every edge <u, v> that we add to the vertex cover, either u or v are in the optimal solution (i.e. in the smaller vertex cover).

Many computer scientists are working to find more of these approximations. There are more examples, but I'm going to stop here. This is an interesting and very active research field in Computer Science and Applied Mathematics. With these approximations, we can get very good solutions for very hard problems by implementing pretty simple algorithms.

Conclusions

In this post, I made a shallow introduction to greedy algorithms. We saw examples of problems that can be solved using the greedy strategy. Then, I talk about some problems for which the greedy strategy is too bad, and finally, we saw an example of a greedy algorithm to get an approximated solution for a hard problem.

Sometimes we can solve a problem using a greedy approach but it is hard to come up with the right strategy. And demonstrating the correctness of greedy algorithms (for exact or approximated solutions) can be very difficult. So, there are a lot of things we can talk about greedy algorithms!

If you enjoyed this post and want me to keep this type of content coming let me know by reacting and/or commenting. You can also follow me on Twitter for more CS-related content.